African culture, also known as Black culture, refers to the cultural contributions of Africans to the culture of their country, either as part of or distinct from that country’s culture. The distinct identity of African culture is rooted in the historical experience of the African people, including the Middle Passage.

African culture for Guyanese is rooted in West and Central Africa, understanding its identity in the anthropological sense, conscious of its origins as largely a blend of West and Central African cultures.

Although slavery greatly restricted the ability of Africans to practice their original cultural traditions, many practices, values and beliefs survived, and over time have been modified and/or blended with European cultures and other cultures that comprise the Guyanese population.

African identity was established during the slavery period, producing a dynamic culture that has had and continues to have a profound impact on Guyanese culture as a whole, as well as that of the wider Caribbean.

Elaborate rituals and ceremonies were a significant part of African ancestral culture. Many West African societies traditionally believed that spirits dwelled in their surrounding nature. From this disposition, they treated their environment with mindful care.

They also generally believed that a spiritual life source existed after death, and that ancestors in this spiritual realm could then mediate between the supreme creator and the living.

Honour and prayer were displayed to these “ancient ones,” the spirits of those past. West Africans also believed in spiritual possession.

In the beginning of the 18th century, Christianity began to spread across North Africa; this shift in religion began displacing traditional African spiritual practices. The enslaved Africans brought this complex religious dynamic within their culture to the Caribbean. This fusion of traditional African beliefs with Christianity provided a common bond for those practicing religion in Africa and the Caribbean.

After emancipation, unique African traditions continued to flourish, as distinctive traditions or radical innovations in music, art, literature, religion, cuisine, and other fields. 20th-century sociologists, such as Gunnar Myrdal, believed that Africans had lost most cultural ties with Africa. But, anthropological field research by Melville Herskovits and others demonstrated that there has been a continuum of African traditions among Africans of the diaspora.

The greatest influence of African cultural practices on European culture is found below the Mason-Dixon Line in the American South.

For many years African culture developed separately from other cultures, both because of slavery and the persistence of racial discrimination in the Caribbean, as well as African slave descendants’ desire to create and maintain their own traditions.

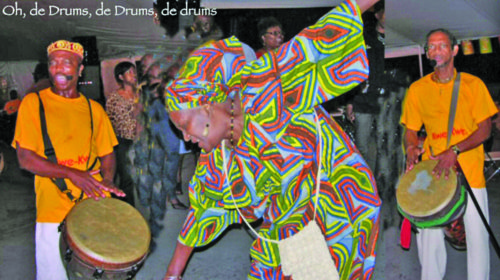

Guyanese Africans in years gone by were known to “draw a crowd” with the traditional “Kwe Kwe” or “Keh Keh” as it is called in parts of Berbice. Most African Guyanese would gather together at the home of a bride the night before the wedding in what is said to be a massive celebration of African/ creole songs and dance. Today, there is hardly any such activity, especially in the urban parts of the country; very few are practiced in the countryside.

Another practice of the African community was the well-known Comfa. Up to the 1940s, some areas were as African as could be expected in the circumstances. Even then it could be found in church hymns and symbols. It seemed focused on the Water Mumma, or goddess of the water. There were stories of fair maid giving combs to earth men for their enrichment and of the men being found with neck mysteriously broken when the union went sour. The full moon and black water were important in the timing and placing of ceremonies.

One thing leads to another, and Comfa ceremonial often leads to fortune telling. The star of the ceremony is the one who will “come through” and after that be recognised and authorised to ‘read’ a person’s future, somewhat like an oracle.

It must have been in the inherited tradition. The practice runs far beyond a race community, just as ‘readers’ of other groups attract African patrons. So it is that healers, readers, workmen and women of one race attract a following that transcends race.

But as African Guyanese become more metropolitan, such things are little openly spoken of or encouraged.